In the same week that the art world was shaken by the news of a hefty 29.6% funding cut in the Comprehensive Spending Review, I headed to Liverpool to check out what is undoubtedly one of the crowing jewels of the publicly-funded arts scene in the UK - the Liverpool Biennial.

The theme of this year's Biennial is Touched, and according to Festival Director Lewis Biggs, it aims to present art with 'emotional impact... that can not only gain our attention but that can move us, motivate us, allow us to find a way to change ourselves.'

My plan was to take in as many as possible of the dozens of artworks that transform the city into a vast gallery during the Biennial - both from the official Touched programme, from the Biennial Independents, and as part of all the other art projects that run alongside. How long did I have to achieve this ambitious goal? One single day - or in actual fact, about six hours. Here's how I got on:

12.30pm: Arrive at Liverpool Lime Street station about an hour later than planned, owing to some unexpected train issues requiring a detour to Wigan, though sadly no pies.

12.45pm: First stop is the Walker Art Gallery, for the John Moores Painting Prize 2010. Now in its 50th year, John Moores has a reputation for offering up a selection of the most exciting new British painting. This year's exhibition also includes works by Chinese artists entered for a new offshoot of the prize - the Shanghai John Moores Painting Prize.

There's a lot to see here, and though the works on display are a mixed bag, they raise some interesting questions about the nature of contemporary British painting. You can read my full review of the exhibition on the a-n interface website here.

1.45pm: Time to set off down Renshaw Street. Taking over the empty spaces of the city is a hallmark of the Biennial, and so its no surprise to find the windows of Rapid (an old DIY store) transformed with anti-consumerist slogans by the Freee art collective. Further on, two giggling semi-naked students pose awkwardly as real-life mannequins in the window, their skin daubed with corporate slogans, for Daniel Knorr's The Naked Corner.

Both these works are part of Re:Thinking Trade, a strand of the Touched exhibition which also includes Lee Mingwei's The Mending Project, (above), in which visitors are asked to bring items of clothing that need mending, and keep the artist company whilst he fixes them. Rather than making the repair itself invisible, instead the process of mending is celebrated and marked with multi-coloured embroidery stitches, using the brightly-coloured threads that create a web around the space, connecting children's teddy bears with items of well-loved clothing.

Close by, Meschac Gaba has created The Souvenir Palace (above) - a souvenir shop with a twist. Here, souvenirs are displayed alongside the accumulated detritus of everyday life, all painted in the colours of different national flags. The shop is intended to function as a trading post, so visitors to the exhibition can bring along their own personal items to be painted and swapped for those on display, in a fun riff on the commodification of national identity, and the mass production of stock souvenirs.

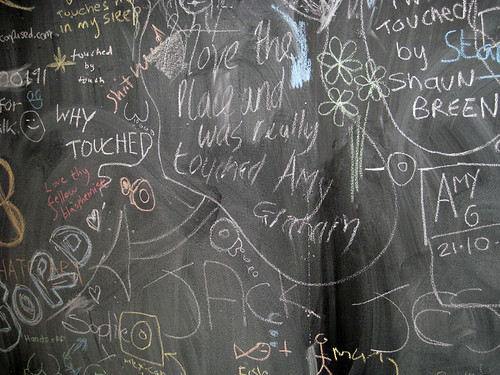

2.15pm: Also at Rapid is the Biennial Visitor's Centre (above), which transforms the disused space into a bustling faux woodland grove, dotted with sheds painted in pillar-box red (below). Blackboards provide a space for visitor feedback, as well as information about the day's events and happenings, and visitors can also explore artworks such as The Marx Lounge by Alfredo Jaar, which includes three copies of every work ever written by, or about Marx, complete with comfy sofas should you wish to peruse them.

Downstairs in the basement, a labyrinth of empty, atmospheric corridors lead us to encounter Trill-Ology, a disconcerting video installation by Texan artist Ryan Trecartin, recommended to me on Twitter by @sheshark. Here, the artist and an accompanying gaggle of shrieking, gender-bending miscreants, smeared in make-up like extras from a horror movie, perform in an extraordinarily inventive trilogy of garish video pieces - a relentless, hectic mashup of plane crashes, LA-style pool parties, soliloquies, hissy-fits and stripteases that play out like a reality TV show on acid, creating an uncanny contrast with the silent spaces of the Rapid basement.

3.30pm: After a quick pitstop for lunch (an essential item on the agenda), it's time to head onwards to the Anglican cathedral, where the Oratory is playing host to The Temple of a Thousand Bells, a installation by Brazilian artist Laura Belém, recommended to me as a highlight of the 2010 Biennial by @alistairbeech.

The chilly white space of the Oratory is the perfect venue for this ethereal installation in which glass bells are suspended invisibly from the ceiling, alongside a haunting soundtrack of music and the legend of an island temple that sinks beneath the sea.

4.00pm: Next stop is FACT, but en route we spot a wolf (the distinctive logo for this year's Biennial, created by Carlos Amorales) and make a detour into 106 Wood Street, an empty garage that has been transformed by Raymond Pettibon into a 'mixed-media environment' incorporating the animation Sunday Night and Saturday Morning (2005), as well as wall-drawings alongside pre-existing graffiti.

4.20pm: On to FACT, where artwork by Finnish artist Karinaa Kaikkonen has taken over the foyer space. For Hanging On to Each Other (below), Kaikkonen collected second-hand clothing from people all over Liverpool to create a colourful washing-line style installation.

In the gallery spaces themselves, Yves Netzhammer's Dialogical Abrasion is an uncanny, alienating experience: an installation with jarring sound and lighting effects, creating a fractured and uncomfortable environment.

Meanwhile, Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980 – 1981 (Time Clock Piece) is an incredibly intriguing recreation of the artists original performance piece, in which he took a photograph of himself every hour, on the hour, every day for a year. Although the work on display here is merely documentation of the performance itself, there is something fascinating about contemplating the thousands of images and time clock punch cards Hsieh created over the course of the year, which completely cover the walls of the gallery.

5.00pm: At the Bluecoat, where we pause in the café for much needed tea and contemplate the (empty) Bed-In, a recreation of John and Yoko’s famous 1969 peace protest, which is hosting a new action by performers, artists and others each day.

Next up are the galleries themselves, where we encounter Daniel Bozhkov's recreation of the Liverpool FC dressing rooms for his installation Music Not Good For Pigeons and Ranjani Shettar's understated installation for the Vide.

My favourite work here, however, has to be Nicholas Hlobo's Ndize, a playful installation that leads visitors through a maze of brightly coloured, densely hanging ribbons that hang from the floor to the ceiling. Part sinister funfair, part innocent game of hide-and-seek, this is a genuinely disorientating and entertaining experience - the perfect end to our Biennial odyssey.

6.00pm: It's time to head home. There's so much more I wish I'd had chance to see... Do-So Huh's Korean House, more Touched offerings at Tate Liverpool and in the public spaces of the city, Bloomberg New Contemporaries at A Foundation, not to mention some of the many events and 'happenings' that have been taking place throughout the Biennial period... but there's only so much art you can realistically fit into one day, or in fact a mere six hours.

Final thoughts on this year's Biennial? There's an incredible range of work here, but for me, what makes it extra-special is the way we encounter it in unexpected places and spaces across the city. Perhaps that's why during the Biennial, Liverpool feels more like a playground than a conventional art gallery, full of idiosyncratic and exciting artworks to discover and engage with. Much of it is baffling, but some of it is brilliant; for me at least, the final word has to go to Adrian Searle, in his review of the Biennial for the Guardian: ‘There are things I do not understand – but sometimes this doesn’t matter.’

So did you visit this year's Biennial? What did you think of it - and what were your highlights?